Introduction

In April 2023, I was approached to instruct a new d.School elective course in the Spring - Design for Health: Building Early Relational Health.

The purpose of this course was three-fold:

Introduce design thinking to students in a fast-tracked, project-based framework over the course of 2-3 weeks

Experiment with a new co-design structure in which the project interviewees are also project designers

Observe and document ways in which this course might become a 10-week full-term course in the future

While the course was officially listed and had a sponsor (Lee Sanders, Professor of Stanford Pediatrics), it did not yet have a day-by-day game plan for how the students might learn and practice design.

With only a few weeks to go, how were we going to hit the promises of this course listed in Stanford’s Explore Courses?

Getting Started

I first met with Lee to understand his intentions and progress for the course. Over the course of a lunch, we had quickly become friends and mapped out what the course might look like on a macro and day-to-day level. Lee had already done plenty of work engaging a project sponsor (e.g., Reach Out and Read), local healthcare providers, and patients for students to interview.

Given the shortened class structure, it was important for us to narrow the scope of the course content to make sure the students could wrap their arms around a project in 2 weeks. “Design for Health” and “Design for Early Relational Health” are both very broad topics that could quickly spiral out into a million directions. After some back and forth, we chose to encircle the design challenge around a singular, universal (in the United States) event:

How might we redesign the 4-month infant checkup so that early relational health between child and their caretaker(s) is improved?

What We Did

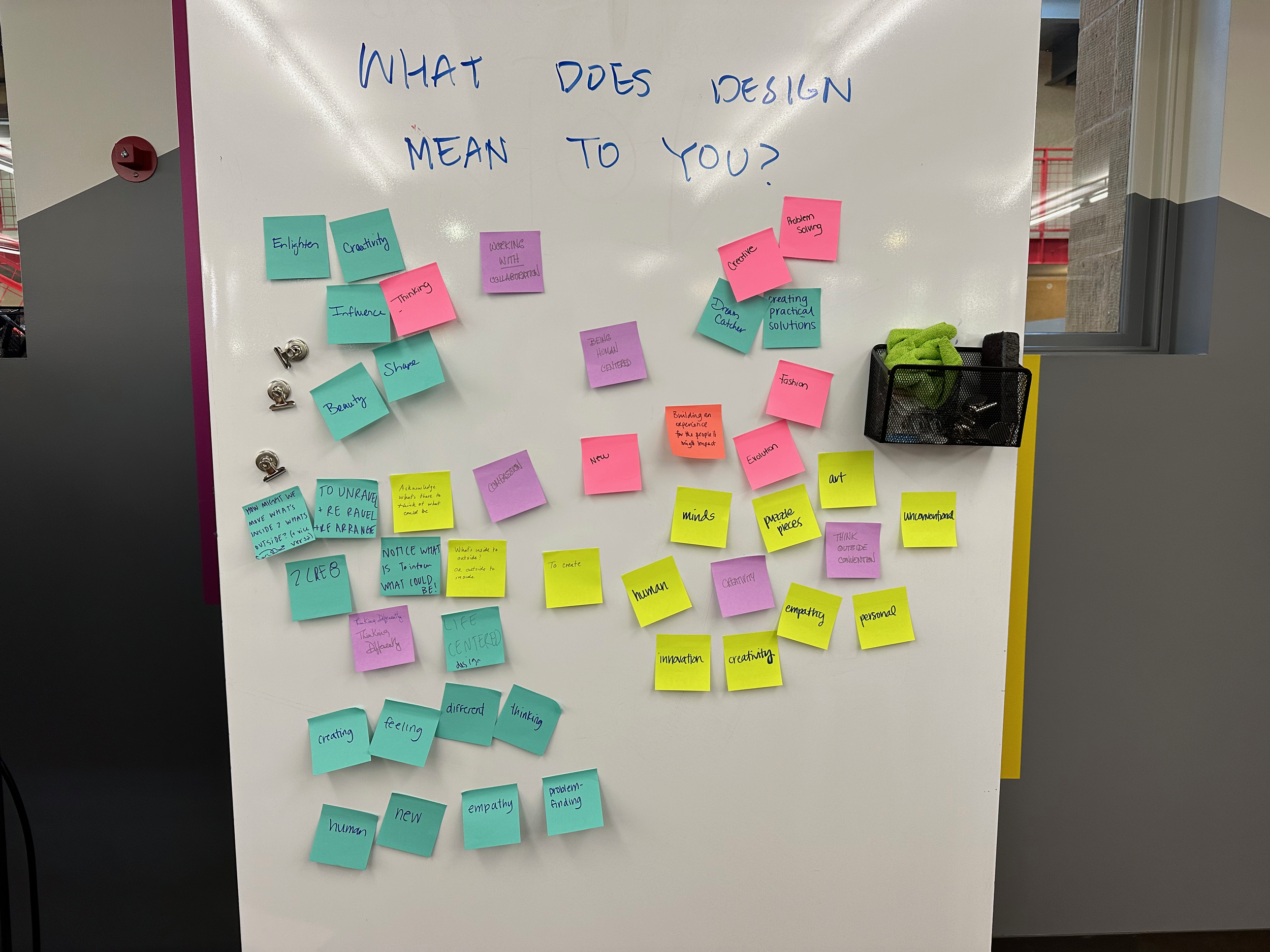

The main structure of the design content revolved around a modified and extended version of the d.School Starter Kit.

By integrating the Starter Kit with the course project for 3 consecutive days, the students learned about design and healthcare simultaneously. For time’s sake, each section of the starter kit was tailored towards the course project.

Here are a few examples of that integration:

Day-In-The-Life Journey Mapping - Students were asked to focus on the last time they received care with a healthcare provider. Stanford design students were then asked to interview their parent design students about the time they took their child in for their 4-month check up.

Crazy 8’s 4’s Quick Solutions - Students were provided constraints (e.g., a cheap solution, a quick solution, a money-is-not-important solution, a solution with robots and AI) and asked to reimagine the 4-month check up experience for their parent designers.

Field Trips - In-between Tuesday and Wednesday, students visited 2 local clinics to interview healthcare providers about the 4-month checkup experience, as well as early relational health overall. Beforehand, we gave students an overview about interviewing best practices (i.e., avoid leading questions, follow up with “tell me more”, assign an interviewer and a notetaker).

The final presentations were a hybrid of in-person and Zoom, to accommodate for the non-Stanford parent design students who lived across the U.S. Each student group had 10 minutes to present, including Q&A from a panel of early relational health experts from Stanford Pediatrics and Reach Out And Read.

To ensure that students had sufficient guidance for their final project, I created a 3-slide template that they could use to organize their presentation. To further underscore the “user” in user-centered design, the template followed a single-user storytelling structure.

Lessons Learned

While challenging, it is not impossible to practice participatory design (a.k.a. co-design) with stakeholders as designers. Equity requires some pre-work

It was quite refreshing to combine Stanford students with non-Stanford parents and take them both through the design process. That said, it was quite clear that participation was not equal across the board. In (very casual) exit interviews, a few of the parents expressed that they had felt intimidated to speak up whereas a few Stanford students wished that the parents had more of an understanding of design thinking fundamentals.

All activities need to reinforce the project challenge

The original design challenge was around a singular event that nearly all babies born in the continental U.S. experience - the 4-month checkup. Although I had articulated that at the start of the term, I did not fully reinforce this before, during, and/or after every field trip / class reflection / class activity. As a result, none of the 3 final presentations addressed the 4-month checkup. While this may also suggest that the design challenge was too narrow, I’d like to think that there were more lessons learned on my end about tying back the class curriculum to the original design challenge.

There needs to be more of an emphasis on storytelling

Storytelling can make or sink a final readout of the design process. While I’m immensely proud of all of my students for telling compelling stories, I wish I had spent extra time in class taking them through a segment on how to tell a story from the lens of their stakeholder(s).